Turns out the Indians (Native Americans) in New England are not all dead or gone. I’ve met many in recent years, and they are definitely alive and real. I grew up in a small town in CT, on the side of a mountain; on the ridge above us was “Metacomet’s Trail” – the name of an old Indian path, we were told. Not much more; and not taught in school. Metacomet, the lore was, had attacked some early English settlers nearby, for no particular reason, except he was a fighter – who was defeated. End of war; end of family; end of Indians. And yet, I’ve met one of his descendents (through his sister’s line). His relatives are still here; I’ve met them and seen their family trees. Others were sold into slavery to the Caribbean; they too are not gone, and remember their heritage. According to that version, he was a Wampanoag leader, son of Massasoit who greeted the Pilgrims in 1620, and was fighting against being pushed off native land. Killed in the war, his body ended up in Plymouth, his head on a pole for 20 years as a warning. Turns out – there are plenty of indigenous people, tax paying voters, who have always lived in New England. In past generations, many kept a low profile – for good reason. Today, look around, there are plenty of ways to see and learn more about our indigenous neighbors, the original residents of this place.

Turns out – we had plenty of slavery here in the north, in New England, that I never learned about growing up. It was always a matter of the South being slave-owners, and racist. But slavery was here, and then erased – no one to document and tell the stories. Owning slaves was on a smaller scale – not plantations, but still a fact of life. Yes-- enslaved people helped build and farm this area – allowing greater freedom for their masters. Some New Englander’s profited greatly from the slave trade (especially banking), outfitting ships, and purchasing cotton from the south. Enslaved men in Bedford and Concord, and neighboring towns served in the Revolutionary war.. Some but not all were given their freedom; they are buried in a separate part of the old cemeteries. Perhaps most shocking, to me, was visiting the Isaac Royall house in Medford, maybe 20 minutes from here: to see the old colonial mansion, still standing. And the extensive slave quarters, still standing – mainly because the estate fell into disrepair and no one had money to renovate – or cover it over. Today, it’s open as a museum, and the picture of life for enslaved people who lived there is not very happy.

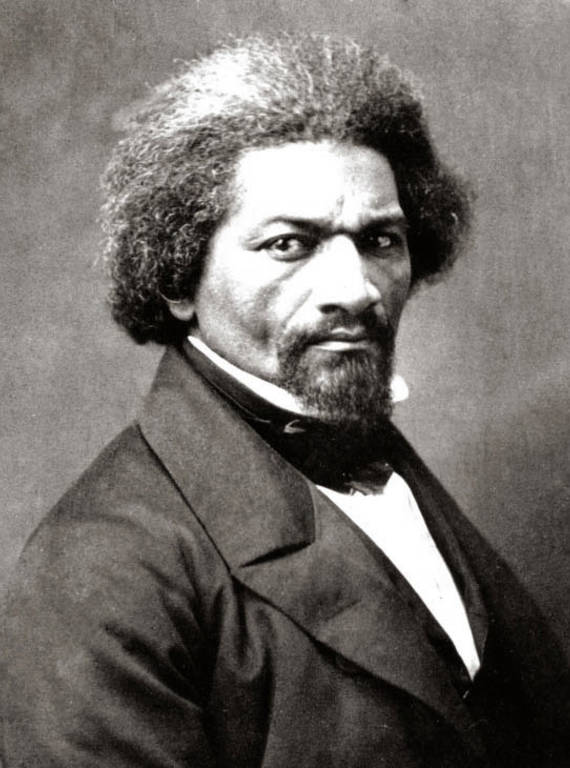

Maybe the worst reality check for me was learning about Frederick Douglass, the great Black abolitionist, and his time on the Eastern Shore. Turns out I lived for about a year in the exact same area as he did, traveling the same roads into the same towns. Only, I had no idea at the time. Not a clue. Never a word, plaque, sign, statue, write-up in the library, etc. that he had been there during a formative time of his life before he escaped. I was an avid user of the library, and interested in local history: the Quakers, the watermen, the chicken farmers, all that good stuff.. But nothing about Frederick Douglass. I found out only by accident, in grad school at Harvard, reading “The Narrative of Frederick Douglass” for an American Literature class. He took great risks to his freedom to name names and places. But they did not want to remember him. Today, there is a memorial to him, in Easton, MD, which I have not seen, but understand it came about as result of a student’s research paper, and quest to bring Douglass, a hometown son, some recognition.

History is a funny thing – an amalgamation of truths, science, records and documents, interpretation – and manipulation. At a lecture on WWII navy history some years ago, the presenter was showing slides of recently declassified images of the action in the Pacific – things were going badly; the news was demoralizing, and so hidden. There was an attack on one of the navy ships; several WWII navy men in the audience had been on that ship, during the incident. The historian described what was officially recorded; and the servicemen corrected him. The historian took down notes, and history was rewritten.

That’s how it goes with history: often written by the victor, and corrected with time and effort for those who want to set the record straight.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed